Davorin Kuljasevic is an international grandmaster born in Croatia. A graduate of Texas Tech University, he is a highly experienced chess coach known for his astute observations of current worldwide chess trends. He has written several books on chess, including an upcoming biography of the current world chess champion, Ding Liren. His bestselling book “Beyond Material: Ignore the Face Value of Your Pieces and Discover the Importance of Time, Space and Psychology in Chess” was a finalist for the Averbakh-Boleslavsky Award, the best book prize of FIDE, the International Chess Federation. He currently resides in Sofia, Bulgaria.

In the interview below, he makes fascinating observations to Ricardo Guerra about the development of the Chinese and Indian chess schools, the roles of Magnus Carlsen and Bobby Fischer in chess history, the importance of psychology in sports, and the influence of the internet and technology on the future of this ancient game.

RICARDO GUERRA: Is there one player you believe will dominate international competition in chess within the next few years?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: I don’t see such a player yet. It’s Carlsen for now, although he seems to be showing some signs of slowing down. Some years ago, I thought it would be Alireza Firouzja, who has the right talent to be a dominant player. However, currently, I am not so sure anymore, since his dedication to the game is tenuous. We might be entering a super-competitive era where many contenders will fight for the No. 1 spot but no one will dominate for a few years.

RICARDO GUERRA: Can we make the case that Magnus Carlsen is the best chess player the world has ever seen? Why or why not?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: If we analyze Carlsen from a purely playing perspective — the quality of his play — he is probably the best player ever. Grandmaster Larry Kaufman published an exciting analysis where he compares the accuracy of the moves of the world’s top players throughout history to the chess engine (https://www.chess.com/article/view/chess-accuracy-ratings-goat), confirming this. Carlsen’s style is closest to [Anatoly] Karpov’s and [José Raúl] Capablanca’s, but he is superior to them and most other world champions in the accuracy of his moves. This is natural, considering he’s had the benefit of studying chess with vastly superior resources (including working with engines) and playing regularly against other very accurate players ([Fabiano] Caruana, [Ian] Nepomniachtchi, Ding [Liren], etc.). Inevitably, these experiences and his unique chess talent helped him raise his game to a quality that no other player in history managed to sustain for such a long time ([Garry] Kasparov being the closest).

Another important point related to this conversation is the length of a player’s domination over the chess world. Carlsen has done this for over 10 years in the most competitive era of chess history. Kasparov had a 20-year period of domination, with solid competition against Karpov and [Vladimir] Kramnik. However, the 1980s and 1990s were relatively slower-paced eras, so Carlsen’s and Kasparov’s periods of power over chess seem comparable. In my opinion, Kasparov is a close second to Carlsen in the “best chess player in history” debate, and [Bobby] Fischer is the third among equals, primarily due to his very short reign. All three are among the brightest talents chess has ever seen and unstoppable forces in their prime years.

RICARDO GUERRA: You have a new book coming out about Ding Liren. In our conversation, you mentioned aspects of his personality and psychological demeanor that I thought were interesting. Could you share with our readers what you found?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: The first thing you notice about Ding is that he acts differently than most top chess players. There is almost a complete absence of egoism in his demeanor. He speaks with an unusual humility for someone so successful. David Navara is the only other top player with a similar psychological disposition and that style of communication. The world champion seems vulnerable and fragile, yet paradoxically, he becomes an uncompromising fighter when he plays chess. It’s like the “eye of the tiger” awakens in him.

The most famous instance of this is when he declined an implicit draw offer by Nepomniachtchi in the final game of the 2023 World Championship match. Instead of playing it safe, he coolly played a risky-looking move that pushed virtually all match commentators and viewers out of their chairs. In later interviews, he repeatedly claimed that this move was nothing special and implied he would play it under any circumstances. It shows he has nerves of steel when he plays chess.

Another thing to remember about Ding is that he comes from a culture most people in the West still don’t know much about. So, while a lot of his behavior is entirely normal in [Chinese culture], we might find some of it unusual. On a related note, [there is a] language barrier [that] can sometimes lead to misunderstandings between him and the chess audience. But my overall impression is that he has a likable personality, and I hope I have managed to convey this in my book.

RICARDO GUERRA: While researching your book about Ding Liren, did you uncover anything unique about his training methodology or system of preparation?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: The inner workings of chess in China are somewhat of a mystery. They are generally very secretive about their training methods. Any strong player will tell you Chinese [players] play chess differently, but [most] cannot grasp what [that difference is]. The best description I’ve heard is from the super-GM Daniil Dubov, who said something to the effect that the Chinese are great at making less logical or [more] unexpected moves that are still very good. Since their chess community is relatively isolated, they develop a unique style of play.

A Chinese acquaintance of mine once told me that the Chinese chess system relies primarily on concrete study methods such as playing, calculation and analysis, which are supported by chess engines these days. By comparison, there is a greater emphasis on more structured study through chess books, courses and coaching in the West.

Of course, they also study chess’s most fundamental theoretical aspects. And they do invite foreign coaches and players (mainly from Russia) to give their best players training and insight into other chess styles. However, they don’t rely on formal knowledge as much [as] innovative practical knowledge. We are starting to see a similar trend in India, and it seems to bring results.

I would compare that learning method to the neural-network-based chess engine Alpha Zero. This chess program taught itself chess from scratch (relying only on a chess rulebook) by playing millions of games against itself. By contrast, traditional chess engines come with preliminary knowledge such as how many centipawns a particular open file or misplaced piece is usually worth.

RICARDO GUERRA: Are there any other particular elements of the Chinese system of development that may be worth mentioning? What about the use of Chess engines by GMs?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: Ding hinted in his post-World Championship match interviews that he used training methods unfamiliar to most other top players. In other cases, he explicitly said that working with chess engines helped him improve his play.

However, playing out certain positions against a chess engine for training purposes isn’t a groundbreaking idea. For example, the ex-World Champion Veselin Topalov reportedly used a similar method in his ascent from an “average” 2700 to a 2800 player. It’s probably the most psychologically taxing chess training one can choose. This option [is] comparable to punching a boxing bag in the most powerful way you can only to have it ricochet back on you with even greater force.

Unfortunately, we don’t have too much information about Ding’s early years, because what happened in Chinese chess in the 2000s didn’t exactly make headlines in comparison to the 13-year-old Magnus Carlsen crushing his competition in Wijk aan Zee and drawing Kasparov in Reykjavik in 2004.

RICARDO GUERRA: Do you currently see any signs that one country will dominate the international stage at the highest level over the next few years? If so, what would explain that domination?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: There are signs that Indian players might dominate the international stage at the highest level. However, while players from India already dominate on all decks below 2600 (top 150-200), the competition is much stronger at the top level, and barriers to entry are more significant. The top 20 is also somewhat of a close circle, so it’s not easy for aspiring players to get invitations to the most prestigious tournaments.

Nevertheless, the best Indian players are getting the proper logistical support to reasonably go head-to-head with the world’s strongest players. They also get the top coaching, in conjunction with solid financial support, since chess is highly respected in India. I’ve coached several young Indian players, some of whom have become GMs, and I realized their passion and work ethic are unparalleled. The future of chess belongs to this country, although it is difficult to guess whether they will produce another brilliant player like Vishy Anand in the next few years or even decades.

RICARDO GUERRA: In your opinion, can a player reach the GM level using only internet-based or technology-based training methods? In other words, can they reach that level without following the traditional route of training, which focuses on instruction through books and over-the-board play and analysis?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: Some years ago, my answer to this question would have been a definite no, but I am not so sure about this anymore. Since the COVID pandemic, which led to a boom in chess activity on the internet, chess has changed a lot, including the learning methods.

Some seeds were already sown in the 2010s, since chess engines and learning technologies had become increasingly affordable, efficient and sophisticated.

I have worked with kids who have never seriously read a chess book (and don’t plan to, either!) and have much better results than adults who have read dozens of chess books. I am sure many young grandmasters achieved their titles by relying primarily on computer-based technologies instead of the traditional approach. For example, GM Simen Agdestein of Norway recently said one of his young students became a grandmaster not having read a single chess book.

Some of the top Indian prodigies (Arjun Erigaisi, I know for a fact) claim that they have read only a handful of books in their life, and one might become a World Champion soon. By contrast, the current No.1, Magnus Carlsen, is very well-versed in chess literature and is known for his phenomenal memory of important chess games of the past. Compared to today’s ‘next-gen’ of top chess players, you could call him a bookworm! Proficiency in online and technology-based learning methods will be essential in the future. The point is that one learns faster this way. For an older generation, including partly myself, learning primarily via a computer screen might seem challenging to get used to. Still, for a young chess brain, which is a ‘tabula rasa’ when it comes to chess, such learning methods are probably only natural.

A case in point is 10-year-old Faustino Oro of Argentina, who is on the path to becoming the youngest international master in history (if he beats [Rameshbabu] Praggnanandhaa’s record of 10 years and 10 months). He reportedly began playing chess only three years ago. The only way he could have progressed so quickly is by using the most efficient study methods.

RICARDO GUERRA: In your opinion, what is the major explanation for the ascendancy of so many high-level players from China and India?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: China and India are two different stories. In China, the system produces high-level players, while in India, the high-level players make the system.

Since the late 1980s, the Chinese have established a strict hierarchy in their chess community, which resembles the traditional pyramid used in the Soviet Union. You start with a massive base of school players, child competitions, etc.; you pick the best talents in the region and give them the best local coaches. Those who prove to be the most successful in their area will eventually start working with the top coaches in the nation. Finally, the very best will be selected to represent their country in international competitions, and after some time, you will have several high-level players. That’s how China achieved its four-step strategic plan of winning the Individual World Championship and the Chess Olympiads (top team competition) in the men’s and women’s categories within 35 years. Unsurprisingly, Russia and Ukraine are the only two other countries that achieved this rare feat, and they, too, have used this rigid but effective system. The Chinese have shown similar success with this strategy in other sports.

On the other hand, India is an example of how the sheer enthusiasm of the nation about a particular sport can produce high-level players without a formal system. Like the Chinese, they have one significant advantage over most of the world: they are a billion-plus country. However, there is no apparent system of selection of the top talents in India that we see in China. It seems more like the “survival of the fittest,” [a] competition-based system in which the top [players] find their way through the tight ranks of similarly eager and skilled players. That makes them resilient and battle-tested competitors at a very early age. Having coached several young Indian players, I can attest to their passion for chess and natural capacity to carry out [the] complex calculations required to become a strong chess player.

RICARDO GUERRA: Speaking of the influence of technology and the internet on chess, what aspects of those elements had the largest role in augmenting the level of play?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: There are several ways in which technology and the internet can help one study and play chess better. In approximate order of importance:

- Playing online: Online playing platforms offer unlimited opportunities for anyone with internet access to practice their skills. [They allow] a passionate amateur to play more games in a couple of years than someone like Mikhail Botvinnik (three-time world champion in the mid-20th century) in his lifetime. Hikaru Nakamura, one of the world’s top players, quickly played over a million games online and is only 36.

Another important aspect of online play is that you can find good opponents at virtually any time of day or night, from any corner of the world. Some thirty or forty years ago, you could only play training games against people from your town or chess club.

- Chess engines: Working with chess engines has transformed modern chess players and chess itself. First, play accuracy in the opening has skyrocketed over the last few decades. An average amateur who studies opening courses on Chessable.com (the most popular online platform for this purpose) would crush an average amateur from the 1950s in the opening probably 8 out of 10 times.

Second, chess engines have taught us to appreciate the concreteness of the game — how certain moves that may look wrong or seem to violate positional principles can be viable options. Generations of players working with chess engines intensively have developed a similar, nonorthodox approach to the game. Overall, this change is for the good, as it has allowed us to expand our understanding of all the complexities imbued within chess.

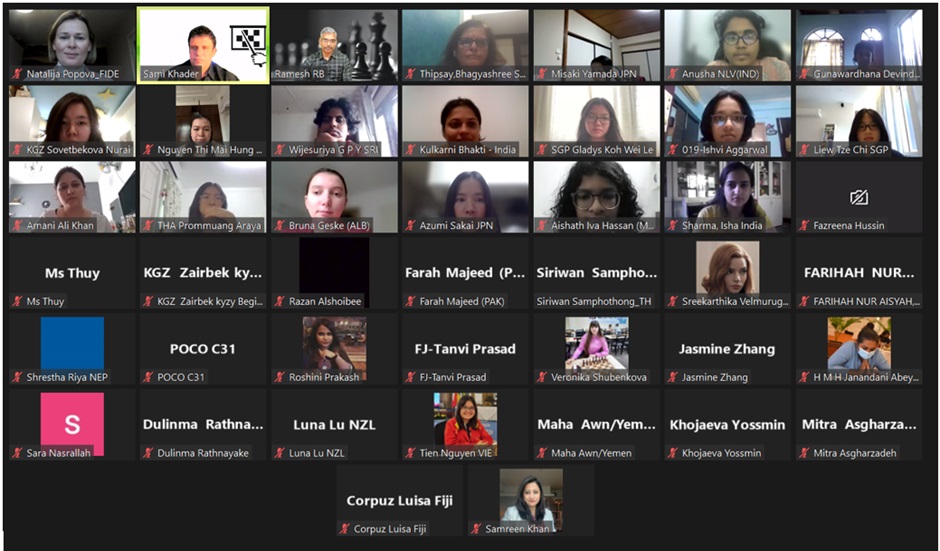

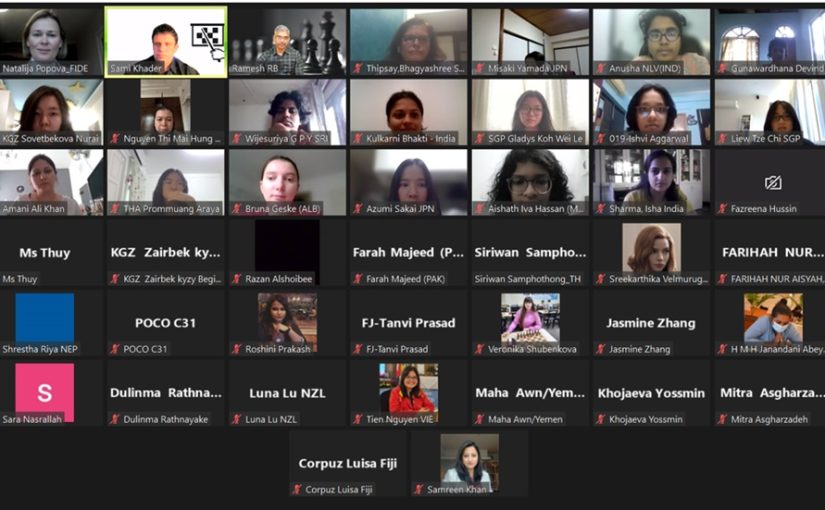

- Online training: Once upon a time, your access to chess coaching or sparring depended on your location. If you were lucky enough, there was a good chess coach or a strong player in your city; if not, you better pick another sport. Fortunately, the internet allows us to connect remotely with coaches and training partners for mutual collaboration. This led to a chess boom globally in the 21st century, as opposed to only in the traditional centers of power, such as the Soviet Union, Hungary or ex-Yugoslavia.

- Chess databases: Stories of older generations of players hand writing their opening analysis in countless notebooks or recording key middlegame and endgame positions on flashcards sound Iron Age from today’s perspective. These days, chess databases allow us to store, update and retrieve vital information quickly. Modern player databases contain millions of recorded games, allowing anyone to study and prepare for their opponent in detail.

- New learning technologies: Advances in technology have allowed creative individuals to develop chess software that facilitates learning. The most famous one is the Chessable.com website, which is based on MoveTrainer technology. This technology, in turn, is based on the spaced repetition learning technique that enables people to [better] memorize information such as opening variations or theoretical endgames. Additionally, some websites use technology to offer convenient visualization and move-guessing training.

RICARDO GUERRA: There are few sports more written about than chess. As we know, the chess literature is deep, meticulously dissecting countless topics related to the game: strategy, tactical elements, openings, middlegame, endgame and history, to name just a few. In fact, writing on chess is so extensive that it has something to teach coaches from vastly different sports, whether about tactics and strategy or the best training methodologies for cultivating standout players. Your fascinating book covers topics related to the best methodologies for training players at different levels. You go into significant detail about how much emphasis they should place on certain aspects of the game, how to optimize study time, and how to avoid inefficient methodologies. In a nutshell, could you give us a breakdown of what a player should do to reach an ELO of 1500, 2000, master level and grandmaster level? What should a player focus on en route to reaching those distinct levels?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: A chess player should primarily focus on sharpening their tactical skills to reach an Elo of 1500, which is considered an intermediate level. Tactical skill is the ability to exploit a temporary advantage that is present in a match. Even the best strategy can collapse in one move if we miss the opponent’s tactic. Fundamental tactical skills [include] proper board visualization, recognition of typical tactical and mating patterns, exploiting the king’s weakness, awareness of the opponent’s move choices, etc.

In order to reach a 2000 Elo, an advanced club player level, a player should have developed more than adequate tactical skills while also enhancing other chess skills such as solidifying their opening repertoire and gaining tournament experience. A player that has reached an Elo of 2000 will have significantly better positional playing, game-opening knowledge, [and] endgame knowledge, but the major difference between a club-level player and one that has reached a 2000 level is tactical skill knowledge. Players in the 2000 range blunder much less than1500s or 1700s.

To reach a master level (2200-2250 Elo), one needs to have developed good positional and strategic skills, being able to plan ahead several moves with more accuracy. One must also possess an ability to methodically exploit minute weaknesses within an opponent’s position that can be turned into bigger advantages. Most of the games played by 2000-level players are decided in the endgame, [so] a master-level player should have decent knowledge of theoretical endgames and a good grasp of typical endgame techniques.

Reaching the grandmaster level requires a lot of work and expertise in all areas. The GM title is highly coveted, and it is an elite level that requires significant training and dedication. The GM norm is out of reach for most players. Since a good 2400-[level] player has already mastered all fundamental areas of the game, to reach the grandmaster level, he needs to focus on the finer points that might be holding him back from making progress. This could be poor time management, inadequate opening preparation, lack of dynamics and risk-taking, insufficient endgame technique, fear of playing higher-rated opponents, poor defensive skills, unprofessional lifestyle, etc. In my opinion, the GM level is characterized by the ability to find the best move almost always and in virtually any type of position of the game.

RICARDO GUERRA: Which players had the strongest influence on your development as a chess player?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC:The first player I studied was Alexander Alekhine. The next player I studied was Garry Kasparov. He was a fantastic role model from whom I learned the importance of solid opening preparation, initiative, and calculation accuracy. I also modeled a lot of my white opening repertoire from Karpov’s games, and studying his games improved my positional intuition and endgame technique. Finally, the fourth player who has had a profound effect on my chess development was Rashid Neshmetdinov. He is not such a well-known figure, but it is enough to know that the great attacking genius Mikhail Tal once said that the happiest day of his life was when he lost to Nezhmetdinov. I was dazzled by his attacking play. He was a greater Tal than Tal himself in mastering sacrificial mating attacks. His match against Lev Polugaevsky will remain one of the most brilliant masterpieces in chess history.

RICARDO GUERRA: Which books had the most significant impact once you reached the master level, were there any books that gave you that final push to propel you to reach the GM level?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC:I almost did not read chess books on my path from IM to GM level—a few books by Mark Dvoretsky. I mainly studied grandmaster games to understand how chess is played at a higher level. However, I will say that Boris Gelfand’s Positional Decision Making was a book that profoundly affected me when I was already a grandmaster. This book is worth pure gold.

RICARDO GUERRA: The performance of Bobby Fischer in 1971 during the Candidates Matches, when he obliterated Taimanov 6-0 in the quarterfinals and Bent Larsen by the same score in the semifinals, was mindboggling. The gap that you saw there between his strength and that of his closest competitors was a watershed moment in chess. And even though his meteoric rise was short lived, since he took an indefinite hiatus from international competition following the final against Spassky, it has never been replicated. In other words, that gap in the final score in that quarterfinal and semifinal has never happened again. Moreover, it would be a challenge for a historian to find such a lopsided score in a consecutive quarterfinal and semifinal in any sport. Could you please comment on what this says about Fischer’s chess-playing ability?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: Fischer’s back-to-back 6-0 match victories against Taimanov and Larsen in 1971 are some of the top performances — not only in chess — but as you mentioned in the history of sports in general. Only Caruana came close to this achievement by winning seven games in the 2014 Sinquefield Cup (with Carlsen and all the world’s best players participating). However, Fischer had a longer, 20-game record of consecutive top-level victories (in the Interzonal tournament before and in the Candidates Final against [Tigran] Petrosian after these two 6-0 matches). Therefore, no chess result in history comes close to his.

Regarding Fischer’s playing ability in these matches, it was clear that he was at his peak. He was a dominant player already in the late 1960s, even though Petrosian and Spassky held World Championship titles in this period. In 1971, he was 28 years old, having reached complete chess and personal maturity. He played chess at the top level for a little over a decade. He was obsessed with being the best player in the world and had the talent and skills to back it up.

While exceptionally strong, his opponents were not up to the task against a Bobby Fischer who was on a mission to win the world title. One of the worst feelings for a chess player is to sense that they cannot make a mistake and to withstand all the changing psychological elements present in man-to-man play. Computers don’t have to deal with these psychological disturbances. I think that Taimanov and Larsen thought they were up against a machine, and they feared making any mistake. Fischer played brilliantly, and Larsen and Taimanov could not handle the psychological and technical forces they encountered.

RICARDO GUERRA: Likewise, in 1970 in the Herceg Novi blitz tournament, Fischer defeated Tal, Petrosian and Smyslov and spent no more than 2½ minutes of his time on any game. Fischer won the event and finished 5 points ahead of the second-place finisher. That result has also never been replicated at that level of blitz play. Could you please comment on the above?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: As I noted above, almost all aspects of Fischer’s excellence aligned in this period of his career. No other player could match him, and he could sense it. That gave him confidence, and that’s why he played so quickly in that blitz tournament. He was so dominant over his contemporaries—a chess player ahead of his time. I believe he would have all the skills to fight the prime Carlsen for the World Champion if we could teleport him from 1971-72 to 2014 or 2019.

Sadly, Fischer’s playing career ended prematurely. He would have asserted himself as the greatest of all time if he had continued this dominance in the 1970s. Some people, especially in the USA, still think he is, but unfortunately, we lack evidence for that since he performed at this high level only for a couple of years. Young Karpov was becoming a force in the mid 1970s, and who knows how their match(es) would have ended. As I noted earlier, Kasparov and Carlsen dominated their respective fields for much more extended periods, and that’s why I give them a slight edge over Fischer in the conversation of who is the best of all time.

RICARDO GUERRA: Ding mentioned in an interview that he is both very emotional and rational. He said that he has to somewhat put aside that more ebullient side of his personality when he is playing chess. In general, this is a very important skill for athletes playing at the highest levels to master; the most successful athletes seem to have an ability to turn their emotions on and off as necessary. For example, Michael Jordan remained stoic when he needed to make a free throw, but he could also display astounding levels of happiness. Comparatively, Lionel Messi maintains serenity when he is about to convert a penalty kick but still shows joy when lifting a trophy. The ability to restrain more extreme emotions in critical situations is of the utmost importance in any given sport, and in certain sports such as archery and Olympic shooting, it can be even more critical. Can you please comment on how this applies to the realm of chess?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: I believe subduing one’s emotions during a high-pressure moment is one of the skills that separates the great from very good or just good athletes. Ding is an excellent example of a very calm and composed player over the board. Among former top players, Vassily Ivanchuk remains one of the few who could have had a greater career had he controlled his nerves better in critical moments.

Chess is slightly different from many other sports in that the internal pressure builds up over many hours of play and usually culminates three, four, five or more hours into the game. I’ve noticed that young chess players can cope with such competitive pressures and general emotional fatigue better than older ones, which is another reason we see chess becoming a young man’s game more than ever in the past.

RICARDO GUERRA: Just last week, the Spanish newspaper AS Sport had a piece about Mohamed Salah, the Liverpool striker, and his passion for the game of chess, in which he states that he plays the game frequently and even possesses a rating. It is my understanding that chess can be therapeutic and help professional athletes take their minds away from stressful situations. It is a game that requires complete and unconditional focus at all times, leading to being in a state of flow, described by the late Hungarian American psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi as a condition of complete relinquishment to the task in front of you. The only thing that matters at that instant is the activity you are immersed in. The passion for a hobby or any activity can be a very powerful weapon, even more so against the superficial distractions and mental challenges of our hypermodern world. In times of tribulation, a passion for an activity or hobby can help people cope. Can you comment on this?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: I firmly believe that chess is one of the best hobbies because it engages many cognitive functions. Besides improving patience and focus and relieving daily stress, as you noted, it also enhances abstract thinking, long-term planning and anticipation of the opponent’s actions, among other things. These strategic skills are precious for anyone from a top athlete to a chief executive. Football (soccer) players like Kevin de Bruyne and Luka Modrić or basketball players like Nikola Jokić and Luka Dončić can see two or three moves ahead before most other players can even realize what is happening at that moment. Knowing the patterns of your game or business and thinking strategically to make the next play is something chess can help immensely.

You made a good point about superficial distractions and mental challenges in today’s world. Playing chess is undoubtedly a better pastime than scrolling on social networks or playing video games, as it engages one’s mind entirely. It can also balance one’s mental well-being, since it allows us to “check out” from real-world issues for a while.

It is known that professional sportspeople have a lot of free time on their hands in between training and games. Picking up chess is one of the best things they can do because its benefits may also help sharpen their focus and other cognitive skills on the pitch or in the sports arena. By the same logic, professional chess players are well advised to pick up a physical sport as a hobby; indeed, many do. Carlsen is the best example, because he has been in excellent physical shape for many years. This gives him a competitive edge over his opponents since he can break them in the fifth or sixth hour of an equal game, as they lose concentration while he remains fresh and fully focused.

RICARDO GUERRA: In an interview, Vladimir Kramnik explained a concept that I thought was very interesting and made me think about an elite goalkeeper I worked with. The Russian chess player said that he is not very competitive by nature and that he is not afraid of losing, so instead he tends to focus on the process of becoming better. Yohann Pelé was the most subdued and in-control athlete I ever had the pleasure to meet. He was a world class goalkeeper and possessed the serenity to execute his craft even in the direst scenarios. I asked him about his demeanor, and he told me he looked at the game of soccer as just a job. Many times, if one is really able to master this approach, it can take away a lot of unnecessary pressure and aid one’s performance. Can you relate to these ideas in any way?

DAVORIN KULJASEVIC: Vladimir Kramnik and Yohann Pelé mention an almost ideal approach for a sports professional. I’ve also read that Real Madrid midfielder Toni Kroos has a similar attitude.

It is clear that to perform at your best, you need to strike a balance between calmness and competitiveness. Too much of one or the other can lead to overly nervous (think Draymond Green’s 2023-2024 NBA season) or overly flat (think aging pro-football players who go to play in some Asian country primarily for money) performances. Some people are naturally calm and focused on their “job” as a sportsman, while others are more susceptible to outside distractions and pressure. That’s where sports psychologists can help a lot.

I wish I could relate to Kramnik’s approach, because it usually brings more success in the long run and is also healthier. Indeed, when I was a kid and a young teenager, chess was a fun game, and I had a similar approach to it. However, the older I got, the more pressure I felt to perform well instead of enjoying the process. I believe many chess professionals face similar pressure. A lot of this pressure comes [from having to make] your [living], because prize money in tournament chess is not big, and margins for error are very small.

However, it’s not only about this kind of pressure, as you can sometimes even see chess amateurs fidget and shake uncontrollably when the game is on the line. A game of chess itself is pretty stressful because you can lose everything you’ve been building for hours in one moment of carelessness. From what I’ve observed, super-calm chess players like Kramnik are few and far between.

Ricardo Guerra is an exercise physiologist working with professional soccer teams. He has a Master of Science degree in sports physiology from Liverpool John Moores University. He has worked with several football clubs in the Middle East and Europe, including the Egyptian and Qatari national teams. In 2015, he was the exercise physiologist of Olympique de Marseille when they reached the final of the French Cup against PSG. Ricardo holds the highest coaching license of the Football Association (England) and a UEFA license. He has traveled extensively worldwide, collecting data and quantifying the physiological capacity of soccer players from various countries. The physiologist is a Ph.D. candidate and the author of an upcoming book about Brazilian soccer. His articles have appeared in more than five languages across multiple news organizations. He can be contacted at rvcgf@hushmail.com.